Reprinted with permission from Dan Empfield of Slowtwitch.com – Original article can be seen here. Bear in mind this article was first published on August 11, 2014. Dan’s “Freedom” bike ultimately led to the development and production of the Litespeed T5G, which later influenced the Litespeed Ultimate Gravel model.

In the five years since this article was written, a lot has changed about gravel bike design, and to this day, the evolution of the gravel bike continues. Is there such a thing as the perfect design for a gravel bike? How about components? As interest in this exciting genre continues to grow, the next five years could be interesting. Over to Dan…

Litespeed Freedom

For some months now you’ve been reading on Slowtwitch about a style of bike you’ve never seen in a triathlon. These are called adventure bikes by some, but I don’t like this. What do you do with an adventure bike? An adventure race?

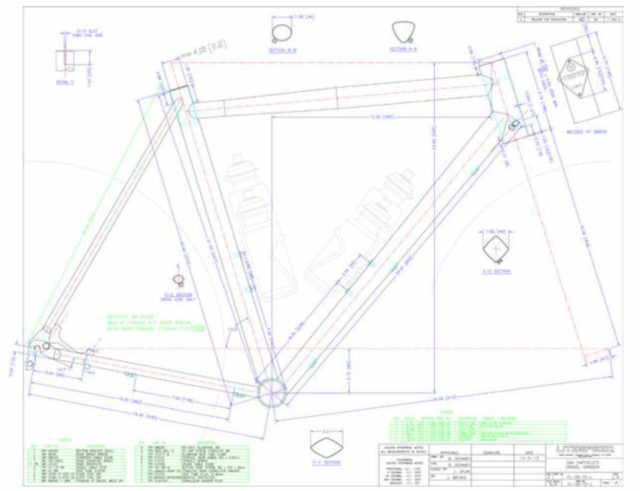

I call it what many others call it, a gravel bike, which is somewhat descriptive at least. I get asked 2 questions pretty quickly. First, how does this differ from a cross bike? I think the bike pictured here is illustrative of the differences, if you ask my opinion. This bike here sits lower to the ground (80mm BB drop), with a longer wheelbase and that’s reflected both in the chain stay and front/center. Further below is a look at the CAD drawing for this bike, click if you want it in a legible size so that you can read it.

The other question I get asked is: If this bike is pretty much like a road race bike in its contact points (mostly just with touring sensibilities built into the handling and balance points), why isn’t a road race bike with substantial clearances for tires up to 33mm sufficient? The answer is, road bikes with good tire clearances make great gravel bikes. Are disc brakes needed for a gravel bike to succeed? No. But I had this bike built to accept either 29” wheels with 33mm tires (or thereabouts), or to accept 27.5” tires with 40mm tires. The latter will roll out – an inflated circumference – pretty similar to the 29er wheels with smaller tires. You can’t do that with rim caliper brakes.

I call it a gravel bike, but what it represents to me is freedom. This is my go-anywhere, do-anything bike. Still, why are we writing about bikes like these? Because of my own view of what multisport is. It’s not swim/bike/run. It’s getting from A to B under human powered locomotion, and making the tools that help me execute that.

My first attempt at a bike like this was a front-suspended, hardtail MTB, a little tighter in the cockpit so that I could slap aerobars on it. I put some 1 1/4” slicks on it. we built a few of those at QuintanaRoo. The Quinterra we called it. We made these more than 20 years ago. I went a lot of places on that bike. Little known fact: That was XTERRA’s first licensed bike, maybe it’s first licensed product.

Steve Hed and I were two of XTERRA’s first licensees and here we are, 20 years later, still throwing parts on bikes like these. This bike features a set of HED Ardennes 25mm wheels built with HED’s disc brake road hubs. On it are Clement 33mm gravel clincher tires and some Shimano Centerlock rotors. This is on an otherwise SRAM Red 22 groupkit and you might ask why I put Shimano rotors on a SRAM/Avid bike. It’s because I didn’t know until Steve sent me the wheels that he uses Centerlock technology for his hubs.

When I put it all together it didn’t work, because Avid’s calipers have these tabs that stick down and bang on Shimano’s 5 rotor arms (the spider that’s kind of like the spider arms on a crankset). So I took some sidepulls and clipped off the Avid tabs. Works okay now.

How did I end up with this bike in the first place? What material should it be built out of, I asked myself. Titanium was the decision I made because I wanted a custom bike – I was particular about the handling of it as well as making sure it fit me – and I wanted a bike that would not easily dent or rust and that I did not have to paint. I called up Brad Devaney at Litespeed and he and I passed notes back and forth until we came up with the design. The CAD drawing below (full size is linked to a few paragraphs above) is the one he created.

Does Litespeed actually make these bikes? Can you go there and order one of these? Not that I know of. But I would like to see them scale up production of a bike like this, because this is really in Litespeed’s wheelhouse.

So, yes, this is a road bike groupkit on a bike spaced 135mm in the rear. Does that work, shiftwise? Yes, with a chain stay long enough and with this bike it’s 430mm, plenty long. [This story originally, incorrectly, read 420mm.] This is needed both for shifting and for heel clearance. Well, my heel clearance. I ride a bit duck-footed, even now occasionally tapping the rear disc caliper with my heel.

This is one value of Speedplay pedals, and I’m just riding Zeros. The “value” I speak of is the ability to very easily set the adjustment on the cleat so that it confines me to inward rotation at the exact point I’m about to nudge the caliper with my heel.

That said, why don’t you look at the Speedplay Pavé? This bike really wants that pedal, I think.

I took pictures of this bike dirty, because this is how I ride it and it should look authentic. Oh, screw it. I just didn’t feel like washing it.

I put about 50psi in the tires if I’m riding dicey offroad stuff mostly. I put about 65psi in the tires if I’m almost entirely on-road or on predictable, dependable trails. I double-wrap the handlebars, that is, 2 rolls of tape. I do this on all my road bikes.

About that handlebar, I started the long hunt for a short reach (70mm), carbon, molded ergonomic bar. I thought I’d have to settle some only some of those features, but I found it on Profile Design’s website. It’s the Cobra Drop Bar, I got myself one of these and now I’ve got to get another because my everyday road bike – a Cannondale Evo Supersix – cannot for my affections compete any longer with this bike, because of the handlebar. Once I put this handlebar on my Cannondale I’ll be riding that bike again, but until I do it’s this Litespeed that comes out of the garage, even for road rides.

This bike was designed to pretty closely match the Cannondale’s contact points. But wait, you might say, there’s a mistake on the drawing! The Supersix in size 58cm (my size) has a head tube length of 175mm, whereas the CAD drawing on this bike shows a head tube 30mm shorter. Ah, Grasshopper, this is where you sit and learn. Brad designed this Litespeed with stack and reach as inputs. When you take into consideration this bike’s lower BB drop, the fact that it’s designed to use the bottom race of a press-in Chris King headset, and the taller clearance of the Enve cross fork used in this frame, you’re left with a head tube that can only be about 145mm in length.

The drivetrain and shifting are SRAM Red throughout except for Force 22 chain and cassette. it’s 50/34 compact up front, 11-32 WiFli in the rear.

The stem is a Zipp, it’s a 120mm -17°. I’ve got an extra 10mm of spacer above the stem just for insurance, but the bike fits spectacularly and I won’t need it.

The bike is sprightly when I’m when I’m out of the saddle because I had it built that way. But it’s straight-liney when I’m riding hands-free and I think it’s because of the long wheelbase.

About the design and geometry process, using stack and reach as design inputs, normalizing for headset bottom races and fork clearances, I bring this up to make a point. It wasn’t only that Litespeed had the technological ability to make the bike I want. Fewer than a dozen bike engineers in the industry understand and could design this bike based on what I just wrote. I might as well be speaking Ugaritic. Brad is fluent in Ugaritic.

This bike doesn’t have a model name. This is the first of its kind out of the Litespeed factory, as far as I know. So I’m just calling it Freedom. It’s the Litespeed Freedom.